Republic of Burundi

If I’ve learned anything in the last few weeks, it’s that fermented foods and beverages are just the cat’s proverbial PJs in Africa, specifically those made from their primary crops. What piqued my interest in particular was Burundi’s version of plantain moonshine, known as urwarwa. I got on the wrong track for a while because most literature refers to it as “banana wine”, so I assumed it was made from what we Americans call “bananas” – specifically the sweet, fragile Cavendish variety that we all grew up eating in our Saved by the Bell lunchboxes.

News flash, Mark! The rest of the world does pretty much everything differently than you do.

It turns out the main variety of “banana” grown in Burundi is what Americans have come to know as plantains – the wiki tells us that: “There is no formal botanical distinction between bananas and plantains, and the use of either term is based purely on how the fruits are consumed,” which quite helpfully puts us absolutely nowhere closer to understanding anything. Regardless: I looked at lots of photos from Burundi and read lots of entries on their agriculture, and trust me – urwarwa is made from “plantains”. Ok?

Ok.

So now: queue my reading an endless series of blog posts, historical accounts, etc. to find a recipe for plantain hooch. Finally, on a long shot, I did a journal search at my graduate school’s library and came upon a miracle: an article entitled “Traditional fermented foods and beverages in Burundi” in the academic journal Food Research International (WHY AM I JUST FINDING OUT ABOUT THIS JOURNAL NOW!?!?) The authors and my personal saviors, Mzigamasabo Aloys and Nimpagaritse Angeline, wrote down pretty much everything except for exact measurements, but this was good enough for me to get started.

So now this had to happen:

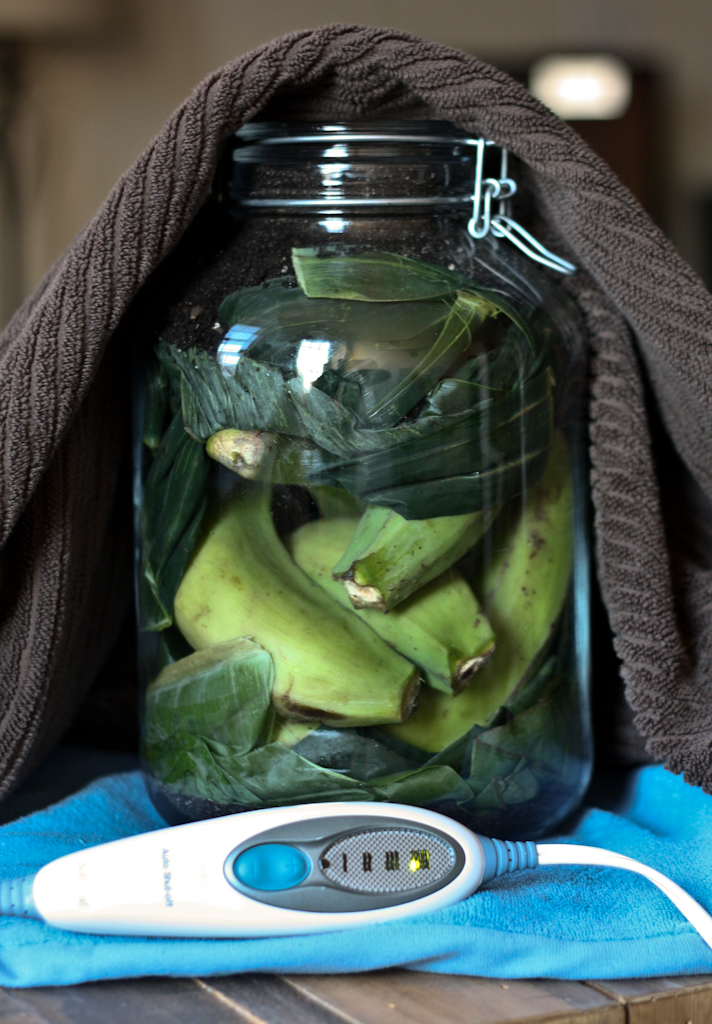

“Green bananas are ripened for 3-5 days in a covered previously-warmed pit lined with banana leaves to insure uniform temperature.” Uhhhhhhhhhh-huh.

OK. What we’re going to do here is get a big jar. We are going to put a little potting soil at the bottom, to mimic the bottom of a pit in the ground. Then we will layer some plantain leaves (found in the freezer section of my Trade Fair grocery store) to make a flat base. Then we jam in as many plantains as we can, put in another layer of leaves to make a closed cavity, and then insulate the top with more soil, like so:

The “previously-warmed” part of the description is referring to the typical method of building a fire inside the pit, letting it burn down to embers, and then using the residual heat to accelerate the ripening of the plantains once they are sealed underground. Since my renter’s insurance is not paid up right now, we’re going to mimic this the safe way by using my girlfriend’s heating pad. Thanks honey!

It’s a little chillier in my apartment than it is in Africa, so we’ll give it an extra couple of days and see those ‘nanners in about a week!

…

Welcome back! Funny story – when you put a bunch of wet crap in a sealed jar, guess what happens.

That’s right – MOLD!

After a week, I had bloomed a major colony of mean-lookin’ spores and interestingly enough, the plantains were no riper than when I had put them in; in short, a big ol’ bucket of FAIL. It just isn’t hot or dry enough here.

Well. Since the point of the burying process is to ripen the plantains, why don’t we just skip ahead and, I don’t know, buy some already-ripe plantains? Sounds good to me. What’s next?

“The ripe bananas are mixed with spear grass.”

Oh for the love of… ok, speargrass, speargrass… riiiiiiight. You must mean heteropogon contortus, indigenous to central Africa. Let’s see – research reveals that this grass is used primarily as animal feed, and as a natural remedy for dysentery and fever. My best guess is that its inclusion in the recipe for urwarwa is mostly to combat the risk of illness caused by the more-or-less unsanitary methods of its production, and not necessarily for any contribution to flavor or texture. I feel confident in leaving it out, since I’m making my batch in a sealed jar inside (and not in the ground outside), and most especially since I’m sure as hell not smashing these things with my feet.

OK, so now a bit of argy-bargy in the mortar and you get this homogenous paste of plantains.

Mix this mash up with an equal part of water in a large bowl or jug, and get in there with your hands to get the starches out of the mash and into the water. Then, strain the solids out and collect the cloudy water in an airtight jar. Dr. Aloys’ recipe states that one part mash-water be mixed with three parts clean water, so that’s the ratio I followed as well.

Then you add in a pinch of roasted sorghum flour to encourage the bacteria, shake well, and wait!

After about three days you’re going to see a big, foamy head appear at the top of the jar. This means that the bacteria in the air has begun turning sugar into ethanol, and that you can start imbibing your homemade banana hooch*.

*I should be really clear about this – DRINK HOMEMADE BOOZE AT YOUR OWN RISK. The potential for optic nerve damage, botulism, illness, death, inadvertent resurrection, etc. is sky-high and I am NOT responsible if you croak. Have fun!

Anyway, after three days you can drink it – it’s still sweet, since much of the sugar is still intact. At five days it’s getting a little gamey and a hell of a lot stronger, but it’s still tolerable. At seven days it’s vinegar – the oxidation process is continuing the whole time it’s sitting in the jar, which means that all that fun-loving ethanol is continuing its degradation into acetic acid (or some other acid, I can’t find much science on banana wine), which tastes sour. This ties in nicely with the description of a 1911 travel guide by German geographer Hans Meyer (translated by blogger Dianabuja) which mentions that, in the time around the plantain harvest when urwarwa is made, people in Burundi get CRUNK for about a month straight – if this is true, it probably because urwarwa does not have a very long shelf-life and needs to be produced quickly before the plantains rot, and then quaffed straight away, before it sours.

Now onto dinner, which seems simple by comparison – a stew of red kidney beans and plantains, accompanied by ubuswage, or pounded, fermented cassava, and something called lenga lenga.

Dr. Aloys saved the day again with another article entitled “Traditional Cassava Foods in Burundi – A Review” – seriously, this guy is the best! He outlined the traditional ubuswage methodology as such: peel cassava; boil; ferment in water for two weeks; boil; pound; wrap in leaves; serve. When you finish, you get a sweet-and-sour smelling ball of gelatinous paste, like this:

You can increase this carbohydrate’s shelf life (in Africa) for up to eight days by wrapping it in a flamed plantain leaf. I gave it a shot for one day.

As a point of record: I opted for ubuswage over the perfectly acceptable accompaniment of rice for two reasons. First, I am insane. And second, the majority of rice currently grown and eaten in Burundi is of dubious pedigree – it’s some kind of ultra-enriched “super rice” that comes from an aid organization, and while that is indeed a great thing I would be unable to get the same kind of rice for my experimenting. What I COULD reliably get was cassava root. Ta da!

Now, to get started on our stew. This is perhaps the humblest dish I’ve made to date; just some red kidney beans and green plantains, an onion, some salt and chili powder and a dribble of red palm oil.

(Ahhhh palm oil, we meet again. I want to love you SO BAD, but when I smell you it just makes me feel like I’m hugging my grandpa in a damp attic with my eyes closed. It is without a doubt the most common lipid in Africa, and much loved at that, but my nose and tongue are still not there – its aroma is rich but dusty, heavy and wet. It has a hilariously low smoking point and it sticks to nigh on everything it touches, so there is no such thing as “a bite that has less palm oil on it”. It endures. It coats.)

Anyway – soak the beans overnight. Fry the onion in the palm oil. Open a window. Add everything else and some water to cover. Stir. Simmer. Wait.

The last accompaniment to our stew, lenga lenga, is actually someone we’ve met many, many times before – our old pal amaranthus. Seriously, are Americans the only ones NOT eating this veggie?? I know we’re all kind of busy with our buffalo wings and bacon cheeseburgers, but JESUS dudes, get on it!

As usual, finding green amaranth in the winter was a fool’s errand, which is the type of endeavor in which I specialize. I tried the Patel Brothers grocery store in Jackson Heights (that’s in Queens), where it might be known by any number of names – I eventually found it frozen as thotakura, but sadly it was already minced and formed into cubes, which was useless for how we are planning to prepare it. Then I tried the mostly-Chinese Pacific Supermarket in Elmhurst (also in Queens), which had the much-more common red-leaf amaranth (not gonna work for lenga lenga…) and, next to it, an unlabeled green veggie that looked similar. When an employee sauntered by I pointed to the veggie and invoked its Chinese name: “shen choy?” He soooort of looked like he heard me but ultimately chose to ignore me, so I asked again – “SHEN CHOY!?” He looked at the leafy stalks and mumbled what sounded like “shen choy, yeah, yeah, shen choy.”

My heart alight, I strode over to the register and asked the young girl who was ringing me out, “shen choy??” You guys, I was speaking CHINESE!!! She gave me that same sort of unsure look, and quietly said “yeah… shen choy.” OK then! Thanks!

When I got home, I noticed that the receipt actually showed the name of this vegetable in Chinese. Desperate for confirmation, I tore through the internet (the whole thing) and found the Chinese script for shen choy. NOPE. No match. I kept looking for other common Chinese greens, which are shown in a nifty little list here. Eventually, I figured out the little communication breakdown I was having at the store – I had, in fact purchased a succulent bunch of basella alba, also known as saan choy. So basically, I was all like “SHEN CHOY SHEN CHOY HEY YOU GUYS HEY SHEN CHOY HEY” over and over again and these poor people were like “Is this white dude out of his mind? What the hell is he saying? Is he trying to say saan choy??” So, big up to myself for once again appearing deranged in public, this time in another language for a change.

Long story short: I am ashamed to announce that we will once again have to resort to canned amaranth, labeled as callaloo and grown in Jamaica. It’s fine and all, but nothing canned can compare to the fresh version – this summer I am going to cook and freeze all the green amaranth I can find, so we don’t run into this problem next winter.

Right, lenga lenga: you take another onion, some more palm oil and some piri-piri chilis (I’m still working off a now-dwindling supply of frozen piri-piri that I grew last summer), sauté, add some tomato and the lenga lenga leaves and smaller stems. There you have it!

The whole meal looks like this:

The stew, to me, is on the bland side of the spectrum, but that’s because I’m an American who grew up in the eighties and has spent his life eating abominable things that carry adjectives like “EXTREME” or “JACKED” or “ATOMIC”. Taking a more meditative approach to eating this dish led to more sensitivity; beans never tasted more like beans, their skin distinct from their creamy innards, and the all-but-flavorless ubuswage started to carry a sour, astringent counterpoint to the palm-oiled plantains’ sweetness. The lenga lenga would have been SO much better with fresh greens, but at its core it’s not far off from the Italian treatment of veggies that I grew up trying to get out of eating. Except for the palm oil, of course.

A note: Pretty much every blogger who is doing this “cook the whole world” thing has made this bean and plantain stew because it is one of the only Burundian recipes to be found on the internet. I would really love to see Central African cuisine better documented in general – information is scarce and what does exist is inexact and patchy. I lucked out with Dr. Aloys’ two articles, but there HAS to be more…

Burundi, you do a whole lot with very little, and I respect the hell out of you for it. Thanks for the killer hooch and the reality check.

Now you go:

Beans & Bananas

1 cup dried red kidney beans

2 green plantains

1 tbsp palm oil

1 small onion, thinly sliced

1 tsp salt

Hot chili powder or flakes to taste

Soak the beans overnight in lots of water. Drain, place in a pan, cover with water and boil until tender. Drain and reserve.

Peel and slice the plantains. Add the oil to a hot pan and immediately add the onion. Sauté until translucent. Add the beans and plantains to the oil, season with salt and chili pepper and fry for 2 minutes, stirring constantly. Add 4 cups of water and bring to a boil. Reduce to a simmer and cook until plantains are soft and the stew is thick. Serve hot with rice, ugali or ubuswage.

Lenga-Lenga

1 bunch amaranth leaves and small parts of the stems, washed and drained

1 tbsp palm oil

2 small tomatoes, quarted

1 medium onion, thinly sliced

Salt to taste

Hot chili pepper to taste (piri-piri is preferred)

Add the palm oil to a hot pan and immediately add the onion. Sauté until translucent. Add the amaranth, salt and chili pepper and toss to coat. Add the tomatoes. Reduce heat, cover and simmer for 10 minutes. Serve hot as an accompaniment.

Ubuswage

For two servings:

1 large yuca/cassava root, peeled and sliced into thick rounds

2 large plantain leaves, quickly passed over a gas flame (or briefly boiled)

Place the cassava slices in lots of boiling water, and cook for about 40 minutes. Drain and let cool. Carefully remove and discard the central fibrous filament from each slice – it will run through the center of the slice and will be tougher than the rest of the flesh.

Break apart the remaining flesh and submerge in a large container of water (I used a big Tupperware container). Change the water after 2 days, and again after a week.

After two weeks, drain the cassava flesh and place again in boiling water. Cook for about 30 minutes.

Drain again, and, while still hot, pound in a wooden mortar until the consistency is gummy, sticky and completely homogenous. Form into 2 balls and wrap tightly in plantain leaves.

Serve at room temperature, as both an accompaniment and as a utensil.

Sources

Aloys, Nzigamasabo & Nimpagaritse Angeline. “Traditional fermented foods and beverages”. Food Research International, Volume 42, Issues 5–6, June–July 2009, pp. 588-594.

Aloys, Nzigamasabo & Zhou Hui Ming. “Traditional Cassava Foods in Burundi – A Review”. Food Reviews International, Volume 22, 2006, pp. 1-27.

http://www.ars-grin.gov/cgi-bin/duke/ethnobot.pl?ethnobot.taxon=Heteropogon%20contortus

http://www.ars-grin.gov/cgi-bin/npgs/html/taxon.pl?18953

http://www.krugerpark.co.za/africa_spear_grass.html

http://newafricancookbook.blogspot.com/2011/04/burundi-comfort-food.html

http://dianabuja.wordpress.com/2011/03/09/cow-grease-meat-and-pate-traditional-burundian-cuisine/

http://www.celtnet.org.uk/recipes/miscellaneous/fetch-recipe.php?rid=misc-beans-bananas

Click to access Element-4-1-FactSheet-17.pdf

http://books.google.com/books?id=LohMBqO3nBYC&pg=PA149&lpg=PA149&dq=Urwarwa&source=bl&ots=AiHttsD0bE&sig=3oLvcTLNYHBvO1zht-DgjxiJKsk&hl=en#v=onepage&q=Urwarwa&f=false

http://books.google.com/books?id=CdLuaG_3LowC&pg=PA43&lpg=PA43&dq=burundi+cookbook&source=bl&ots=iqt6UKaejC&sig=seaA_dAEOZKrfZ5yE6ibsQTW-Zc&hl=en#v=onepage&q=burundi%20cookbook&f=false

http://dianabuja.wordpress.com/2011/05/14/brewing-banana-beer-in-colonial-burundi/

http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:Z1tqX9lD2T8J:www.answers.com/topic/east-africa+&cd=4&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us&client=firefox-a

http://dianabuja.wordpress.com/2012/06/16/banana-beer-and-other-fermented-drinks-in-africa/

http://www.congocookbook.com/beverages/pombe_tembo_and_mawa.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Banana_cultivar_groups#AAA_group

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plantain

http://www.wisegeek.com/what-is-banana-beer.htm#

http://www.irri.org/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&id=10739:rice-in-burundi&lang=en

http://agro.biodiver.se/2011/12/where-burundis-new-rice-comes-from/

http://dianabuja.wordpress.com/2009/08/13/the-social-life-of-beans-in-burundi/

http://www.celtnet.org.uk/recipes/miscellaneous/fetch-recipe.php?rid=misc-beans-bananas

http://dianabuja.wordpress.com/2012/11/16/amaranth-greens-lenga-lenga-politically-correct-easy-to-grow-and-delicious-recipes-included/

http://www.localbanquet.com/issues/years/2010/summer10/newamericans_s10.html

http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Cookbook:Amaranth

Loved reading this post! It was entertaining and made me laugh on so many occasions. I applaud your adventurous spirit on this! Can’t wait for the next post 🙂

THANK YOU!!! Oh man, it feels so good to hear I made someone laugh 🙂

Keep reading!

Mark

What a great entry! McDonald’s in Mumbai (don’t judge, i had to try it) had packets of piri piri spice that you could shake onto your fries that made them taste incredible! Just like Hot Fries! If you’re a true piri piri fan, I’ll share a packet with you 🙂 I brought home 20. A request that made them look at me like I was crazy so I know that feeling! Keep up the good work!

DO WANT. Thanks Shannon! We are owed a hang, pronto! 🙂

Almost died when I saw there was a new post. Loved it, keep going ! ❤

Micheeeeeele thank you thank you THANK you 🙂

Thanks for referencing my blogs! 🙂

Thanks for writing them! They represent the best information available on the cuisine of Burundi on the internet! You should write a book!!!

🙂

-Mark

Oh! Well! Thought about that, but – at least – not for now.

Well if you ever do, I’d like to buy the first copy 🙂

How about being a pre-publisher reviewer? (if i ever proceed with a book….

I would be honored!!

Here again researching. Burkina Faso went reasonably well and it seems a no-brainer to do the beans and plantains dish. Also, I have yet to lay eyes on fresh amaranth greens anywhere. Like you, I’m stumped on how it can be everywhere but here. At least at this time of year.

Thanks again for traveling the road ahead and your exceeding devotion to detail!

And the laughs, too!

Hey Cliff! Amaranth season should be just around the corner for us in the Northeast (although at 33 degrees in April, I’m beginning to have my doubts…), but for you in Florida I would have hoped it could be year-round. Any farmer’s markets you can try? As I’ve shown, there’s always the detestable canned “callaloo”, but blechhh… it tastes like tin.

I have really enjoyed your site as well, and your learning experience – I’ve been cooking a long time and even I feel out of my element at times. For a beginner to even attempt some of my advanced-lunatic dishes is very admirable! 🙂

Keep in mind though – I tend to pick the weirdest or most distinct dish that I can find, which means your husband will indeed be eating some things that he will categorically NOT like. In those cases, you might be better off ignoring what my deranged mind has led me to create, hehehe. There seems to be a good rice/wheat/corn/plantain dish for every country, if you ever get stuck.

Thanks for reading and GOOD LUCK!

Mark

I love amaranth leaves. Can you alert me if you find any in NYC? (Maybe we should buy out the whole stock and freeze them?) They’re used a lot in Central Mexican cooking — called “quintoniles” and wonderful stewed in red or green chile sauce. The purple-tinged Chinese version is different and not as delicate or sweet.

Lesley! I see them all the time in full summer at United Bros. and Trade Fair (30th Ave.) – I’ll definitely let you know when I run into them. I’d definitely be down for buying, par-boiling and freezing – I’d planned to do that the last two summers and then got lazy 😉

The purple one is tasty, too, but you’re right – it’s used more in Indian and Southeast Asian cooking. My post on Brunei has them featured prominently!

Great talking to you yesterday, and thanks for checking out the blog!

Mark

Pingback: Burundi | Cooking Around The World